Around the time that everyone else my age was really getting into flash games I was rummaging around in the dusty basements of the internet for abandonware and freeware, learning the mysteries of the emulator and becoming acquainted with DOSBox and a variety of early console emulators. In these younger and more impressionable years, I sought to make a pilgrimage through what various threads spat on forums across the earlyweb told me were the greats of the past and learn what made them great.

So I visited and sometimes beat the Zeldas (smashing my face repeatedly into Zelda II before eventual triumph), the Metroids (somehow skipped Super Metroid until much later), Zork, Elite, a bunch of Sokoban-style games, and others before finding my way to some freeware threads in scattered forums. In these old threads I'd first come across games like Dwarf Fortress in its early iterations as well as Liberal Crime Squad, Nox, Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup (a fixation for another day and one that led me down the Rogue hole), Tibia (see previous parentheticals), and many, many others of varying quality. Amongst the sea of games, two would always come up in the same thread as the examples from Japan of great freeware games: Cave Story and La-Mulana.

|

| unrelated sick art for different game |

"... if Cave Story is the sun, then La-Mulana is the moon, and these two works were mainstays of the Japanese indie world." - Hayato Iketani, freelance gaming journalist

So what is La-Mulana? What's this all about? The game is a 2D platformer in the vein of a Metroidvania. The player takes the role of Lameza Kusugi, an Indiana Jones type archaeologist who receives a letter from his father that prompts him to take up his whip and MSX laptop and journey into the jungles to the site of the ancient ruin of La-Mulana. You take up the job of exploring the massive ruin and solving its fiendish puzzles by scanning ancient tablets and solving riddles with only your wit and persistence. The ultimate goal is to defeat the guardians, huge boss monsters, and solve the riddle of this mysterious labyrinth. There are hidden shops, secret passages, cruel traps, dozens of items and ROMs for your MSX, and a even a few encounterable characters within the dungeon. The original release of La-Mulana had blind/un-guided runs take anywhere from 20-200 hours- and it's 2011 WiiWare and 2012 PC remakes are just as challenging with a few gameplay changes and an complete graphical overhaul.

That original release of La-Mulana remained in the back of my head for years though, drawing me back for further attempts. It would grow in reputation all the time as one of the most fiendishly difficult games out there- not necessarily for its combat but for its riddles and puzzles promising early on in its manual a tantalizing challenge:

"As you defeat Guardians and collect Items, you will run into a single,

big riddle. This is the secret of La Mulana! What is La Mulana, and what

is Lemeza researching? We hope that you can use your skill and

ingenuity to solve that mystery."

Simply put it was the premise and mystery of the game that dug its claws into me, its promise of a giant dungeon filled with traps and riddles, challenges and secrets, and the one big secret of La-Mulana at the very end-but I was never able to get very far with it as a consequence of the punishing difficulty (more on this later) and it would sit untouched for a long, long time leaving its tantalizing screenshots and promise waiting for its time somewhere in my head.

Taken directly from the fan translated english patch readme:

La-Mulana is a freeware free-roaming platformer game designed to look, sound, and play like a classic MSX game. It's heavily influenced by the classic Konami MSX game "The Maze of Galious" and anyone who has played that title will probably recognize the similarities very quickly. You play the whip-wielding Indiana Jones-esque archaeologist Lemeza Kosugi as he investigates the ancient ruins of La-Mulana in an attempt to find its treasure and one-up his father, who is trying to get the same treasure as well.

The game is huge, with many different areas to explore and dozens of items and weapons to find. Each area has a large variety of puzzles and traps (many of them quite fiendish) and you need to solve the puzzles in each area to discover the Ankhs and Ankh Jewels, which allow you to fight the eight Guardians of the ruins. To solve the puzzles you'll need to be able to read the tablets scattered throughout the ruins, which will require a Hand Scanner and translation software for the portable MSX that Lemeza has brought along on the adventure. Your Hand Scanner will also allow you to find items and search the bones of less fortunate adventurers.

La-Mulana is one of the longest freeware games I've played in quite some time--my first playthrough took me 26 hours, and even if you knew exactly what to do for each puzzle in advance I'd still bet the game would take at least 10-12 hours to complete, not counting the bonus dungeon.

DEVELOPMENT HISTORY

At the risk of making this into a La-Mulana fan blog, I'll do some brief summation of La-Mulana and its development history as best I can without devoting a whole day to it (CRAB lied as easily as he breathed)- the dread shadow of all-consuming LINK ROT lies heavy on even the Japanese web where it concerns La-Mulana, but I'll do my best armed with only a failing search engine and its translation features.

The team that would create La-Mulana first got together as part of a passion project to create Gradius fan games, calling themselves the GR3 Project. On the team, we have Naramura (Takumi Naramura) acting as the director and having a hand in pixel art, illustrations, and music, Samiel (Tomoryu Samejima) who was in charge of enemy and item design as well as working on the music and programming, and duplex (Takayuki Ebihara) who was the head programmer for the group; each member from a different background and working in unrelated fields, but coming together on an MSX fansite that Naramura ran to form the GR3 Project. For those not familiar, the MSX was a hobby 8-bit computer released in 1983 competing for space with the Commodore 64, Apple II, ZX Spectrum, etc. The MSX line saw use up into the 1990s and was mostly popular in Japan- where Konami would develop the first Metal Gear for MSX hardware.

| |

| From left to right: Samiel, Naramura, duplex, and future Nigoro member Nakagawa |

Their first project was the Gladius doujinshi GR3 which met with some moderate success at the time and was praised for the increased difficulty in the stages. When planning for what their next game would be, the group settled on something like an advanced form of Maze of Galious, a well regarded platformer often compared to The Legend of Zelda and charged players with navigating the enormous Castle Greek and its ten connected worlds to rescue the hero's unborn child from the evil Galious.

|

| Maze of Galious |

According to Naramura, about halfway through the game's development the team made the significant changes that would solidify the staples of La-Mulana. Naramura was taking to the role of head trap-maker at the time but it was duplex who set a "three-phase" approach to level design. The main idea was that the first and second times a player encountered something new they would probably fail the puzzle or encounter and die, but by the third time they should be able to succeed and feel all the more accomplished after having failed. This sort of dopamine-by-trial gaming would be familiar to any fan of older games or the more modern ones that have taken the same sort of challenge to heart as with any From Software game.

Still, the main developments to the style of the game came after reflecting at that midpoint in the development where the team felt unsatisfied at having created what they deemed "a cheap Galious knock-off". As Naramura puts it in the original La-Mulana game manual:

"Naramura wonderd if it might not be possible to

incorporate the sense of tension in newer games like Metal Gear into La

Mulana. After thinking about it for about an hour (Pretty quick!) we

decided to put in the fear of death int La Mulana.

Let's say you were an archaeologist. You're

standing in front of a dark hole that you can't see the bottom of. Would

you jump in? In real life, your response would probably be, "Heck no!"

After all, you don't know what's dow there. Or say you're in a room

filled with corpses and a bunch of switches. Would you just press them

haphazardly at random? In this case too, you'd probably never do

something so reckless. We wanted to try to incorporate this type of

tension--a "Proceed with caution" type of feeling into the game.

Recently--or actually a lot earlier than that, a

lot of games have been set up so that "if you just check everything, the

puzzle is easily solved" and "if you screw up, just reload" and a lot

of people have been thinking, "are these sorts of games really all that

fun?" So what would happen if we took those two trends away from gamers

used to easy games?

With this in mind, we ended up making La Mulana a

lot harder than we had been intending when we started the project. We

tried to make it so that people wouldn't get hopelessly stuck

everywhere, but if you just whack walls at random without thinking

you'll die. If you think "Ooh, a treasure!" and run charging toward it

without thinking, you'll die. If you just operate a mechanism without

thinking about how it works, you may end up not ever being able to get a

specific item. If you think "I'm trapped! I'm going to warp out!" and

do so, you won't be able to get back into that room from the outside.

Once you do finally manage to find your way back in, you may be

confronted with an even more obnoxious mechanism to overcome than

before. If you make enough big mistakes it will even become quite tough

to complete the game.

To be honest, we have our doubts whether or not

people will like a game that has elements like "If you make a mistake

there's no going back" and "There's always the tension requiring you to

think ahead." But at the same time we have confidence that it makes La

Mulana a deeper game for it. Some people may think "this game is a

pain!" But we hope you can find enjoyment with a "to keep this from

being a pain, I'd better think before acting" sort of playstyle. We

think if you use your wits to the fullest, the sense of accomplishment

you'll get when you finally finish the game will all the more rewarding."

This sort of approach of embracing the fantasy of the game and encouraging the player to fear death and consequences and rely on their wit and skill to overcome challenges rings some bells similar to what those in the OSR community seek to emulate in tabletop games. There's a strong vein of the "think before acting" mentality throughout the design of La-Mulana which drives the challenge up for the unprepared and rewards the players who take the time to engage with the fantasy of the game and study their environments.

Huge portions of the game require you to uncover secret histories of the world and piece together their significance to overcome obstacles and progress. This reliance on understanding the dungeon's history reminds me of my takeaways from reading through Grognardia's seminal megadungeon: Dwimmermount, wherein the secrets of the world can be similarly found engraved in walls and hidden throughout the labyrinth. For Dwimmermount, this serves a dual purpose in providing both loot for the players to sell in the forms of architecture and charcoal rubbings, but also to inform on what further secrets can be found in the depths of the dungeon.

|

| This map from the game manual is strikingly reminiscent of early D&D cutaway maps |

The original release was brought to english speakers with its english language fanpatch in January of 2007 where its fame, and infamy, would grow. Even with the patch, there were complaints of poorly translated hints for riddles stopping players from progressing and a good deal of the humor and parodies was lost in translation. Still, La-Mulana was accepted very warmly in both Japan and out in the West.

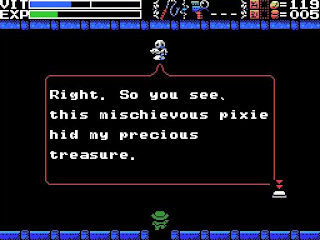

One of the key things to understand when talking about difficulty in the original game is how health works. The player has a vitality stat and an experience stat. Vitality represents your health and you die at reaching zero. In order to expand your max vitality the player needs to use a Life Jewel, extremely rare and vital for the avid explorer, these collectibles can only be found in the dungeon. Your experience is increased by killing enemies and once the bar is filled so is your health. The third and final way to recover health is to defeat a Guardian, one of the field bosses in the game. Taking these three measures into account, the lack of easy access to healing is a huge factor in the difficulty of the game, usually requiring players to find a relatively safe area of the dungeon to grind out enemies until they fill their experience bar.

Saving and transportation are also huge contributors to difficulty. In order to save, you need to speak with one of the main characters in the surface village, Elder Xelpud. This degenerate old man is a key source of rumors and hints throughout the game, but his most crucial function is that he saves your game for you- meaning you have to escape the dungeon to save. And the dungeon is big. Very big. It's seperated into fields which are mini interconnected dungeons of their own with 20 screens in each. On one of these you'll find a transfer tablet that, with the help of the Grail item, can be teleported to at will. So with 1 in 20 rooms being able to be teleported to and your only save point being on the surface (which can also be teleported to) the player needs to plan carefully just how far into the dungeon they're willing to venture before trekking back to the surface to meet with Xelpud.

|

| Cancelled project MSX Kingdom |

With the release of La-Mulana gaining traction, GR3 Project began work on what they planned to be their farewell game. It was called MSX Kingdom and the idea was that as the player progressed through the game the graphics and mechanics would advance similar to the MSX to MSX2 upgrade and even up to the never-released MSX3. However, duplex began to get bogged down with his day job and GR3 Project ended up dissolving on February 1st, 2007, releasing the La-Mulana Editor as their last product together.

However, on May 12th of the same year, the three would come together once again to form NIGORO, the company they still run to this day (Technically NIGORO is the game development wing of the larger company ASTERIZM which may or may not also just be the same three developers). A note on puns here, NIGORO is "256" in Japanese as an homage to the 8-bit nature of their games. The name La-Mulana comes from reading director Naramura's name (in Japanese characters) bacwards, our protagonist Lameza is from Samiel, and Elder Xeplud is from duplex.

The new team would go on to make a series of flash games to hone their skills and expand their breadth (these are mostly unplayable due to the death of flash) and some would get success as releases for consoles in the future, such as the slap-battling romantic drama Rose & Camellia. On July 27th, 2009, the team announced that a La-Mulana remake would be coming out to the WiiWare shop in 2012. Teaming up with Nicalis- who also supported the development and release of the Cave Story remake around the same time, they planned to make this the definitive La-Mulana with a series of changes and updates.

|

| Remake promotional art |

- A healing spring was added on the surface enabling easy healing that didn't require grinding out a few enemies in the dungeon

- You can now save at any transfer tablet and not just with Elder Xelpud

- I can't confirm this but I'm pretty sure your basic attacks are slightly faster and this is a huge change to the feel of combat

- Xelpud provides a new ROM that allows him to email you throughout the game. Although optional, his emails serve to not only flesh out Xelpud and the world but also provide additional hints and direction for players

NIGORO and Nicalis would release the remake in Japan through the WiiWare shop on June 21st 2011, however due to poor sales Nicalis would part with NIGORO, leaving the future of an English edition in jeopardy. Luckily, Playism partnered with NIGORO to bring an English release to North American and European servers on September 20th, 2012 and NIGORO brought La-Mulana back to the PC with a release on July 12th, 2012 (with the best trailer for the game here)followed by a GOG and Steam release shortly later.

This PC version brought another few improvements, namely a revamped Time Attack and boss rush mode as well as USB gamepad support and Japanese, English, Spanish, and Russian language support. The next release would be far down the line in March of 2020 bundled with the game's sequel, La-Mulana 2 for the Switch, PS4, and Xbox One. One last edition worth mentioning is the La-Mulana EX (or Extra) releases for the PS Vita from 2014-2015 which made slight gameplay changes and included a monster bestiary.

And have I mentioned the music? Each field that you explore comes with its own fantastical arrangement that really sets the mood for your dungeon crawl and will worm their ways into your waking world. Whether we're talking about the original SCC releases, the remake releases, or the Journey remixes, the sheer level of quality in the musical compositions is overwhelming.

The accomplishments of this three-man dev group are astonishing, despite some rocky developments here and there along the way, La-Mulana a true monolith in the Metroidvania genre and the indie scene at large- and its mysteries are still waiting to be uncovered.

Now, I'll talk about La-Mulana 2 eventually, but first- what was the goal of this post? I wanted to highlight a wonderful game, but also it served to prepare me for my dive back into La-Mulana (PC release) to finally beat the game. In all my attempts over the years through the various versions the furthest I've gotten (or so I'm told) is about half way. And so throughout the years between delves and the research for this post I've dodged spoilers and guides for the game to preserve the mysteries as fresh as they can be to keep this next attempt at cracking the mystery of La-Mulana as true to intent and form as possible. I might leave some notes or journals documenting progress here or there, so keep an eye out.

Go check it out for yourself, the mystery of La-Mulana is waiting.

No comments:

Post a Comment